![]() historic preservation relies on uncovering—the uncovering of artifacts to reveal and illuminate our past. Rarely is it an act of recovery. In other words, the artifact’s original meaning might be identified and might elucidate a previously unknown past, but its original application to society is often left un-restored. Like an ancient bronze tool displayed in a museum’s exhibition case, the artifact’s relevance remains historical in nature and locked to its period of initial significance—banished from ever playing an active role in our society again. Similarly, when we untangle architectural artifacts from sedimentary layers of successive occupations, we also reduce those vestiges to singular conditions. Simplified and labeled, they make for easy exhibition. Fearful of complicating their perception, clear boundaries arise to confine the object from its contemporary context and the everyday life of the city.

historic preservation relies on uncovering—the uncovering of artifacts to reveal and illuminate our past. Rarely is it an act of recovery. In other words, the artifact’s original meaning might be identified and might elucidate a previously unknown past, but its original application to society is often left un-restored. Like an ancient bronze tool displayed in a museum’s exhibition case, the artifact’s relevance remains historical in nature and locked to its period of initial significance—banished from ever playing an active role in our society again. Similarly, when we untangle architectural artifacts from sedimentary layers of successive occupations, we also reduce those vestiges to singular conditions. Simplified and labeled, they make for easy exhibition. Fearful of complicating their perception, clear boundaries arise to confine the object from its contemporary context and the everyday life of the city.

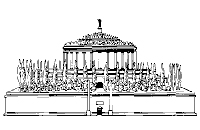

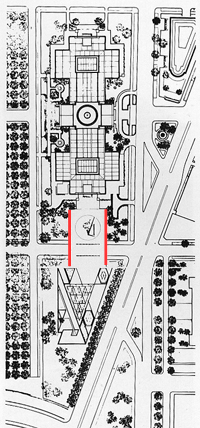

The Mausoleum of Augustus in Rome’s Piazza Imperatore exemplifies this modernist crisis. Originally clad in marble, ornamented and landscaped, this imperial tomb structure dates to 28 BC. Built to house the remains of Emperor Augustus, it spoke of Rome’s glories. In antiquity it was Rome's most important monument. After the empire's fall, its remaining inhabitants stripped this monument of its precious materials. Reduced to its brick substructure, later generations appropriated and transformed these foundations to meet specific needs unique to and reflective of their particular moment in history. For example, in the territorially tentative early medieval times, the mausoleum served as one of the various strongholds of the Colonna family with fortified walls and a moat; in the more peaceful 16th century an ornamental garden crowned it; when Goethe indulged in Rome’s bounty, it was an arena for entertainment such as bullfighting; then in the 19th century a circus, and in modern times this same mausoleum was roofed over and designed as the city's new lavish art nouveau concert hall. Suddenly in 1934 this long vibrant succession of occupations came to a tragic halt.

28 BC

28 BC

28 BC

28 BC

16c. AD

16c. AD

18c. AD

18c. AD

21c. AD

21c. AD

Seeking to uncover tropes of imperial legacy, every shred of these later occupations were stripped by a regime searching to establish lineage to Rome’s ancient Empire. To cleanse the artifact and to provide space for the display of other artifacts, such as the Ara Pacis (the famous monument altar of Augustus), the dictator Benito Mussolini demolished large quantities of surrounding medieval fabric—several city blocks rich in history. So what was once a richly layered focus point that transformed to suit the desires of each new generation, the mausoleum now sits forlornly in a traffic-encircled, moat-like park indifferent to its past occupants and its current neighbors. The deprivation of any real human activity is sad when compared to its outlandish past.

Mussonlini at work

Mussonlini at work

Eager to attract the attention of tourists challenged more by time than intellect; cities readily package thousands of remnants like the Mausoleum of Augustus for easy uncomplicated consumption. Unaware of multiple histories, general audiences easily approach architectural artifacts in their simplified versions assuming these remnants tell a complete and finite story.

Whenever we free an artifact, of its cumulative layers we museify its remains. Reduced to playing the role of passive entertainers, rather than integrated signifiers, such attractions become stumbling blocks within the surrounding urban fabric. This programmatic sterilization of artifacts has affected cities worldwide. This is not necessarily a recent issue, though in cities like Rome it has taken on a certain urgency. The question has gone beyond the issue of appropriateness, to become a question of whether one should even build within historic city centers. By prejudging contemporary architecture as incapable of contextual engagement, cities ultimately label artifacts as impotent. Such an attitude denies the fertility of significant sites to generate and inspire new architectural scenarios. Segregation, rather than engagement, defines this misguided urban strategy.

Of course our inherent patrimony in the United States is relatively different from that of Italy’s, yet our preservation guidelines are equally stifling and dated. Initially heralded by most architects, the preservation movement in America justly solidified during that hard-fought battle over New York’s Pennsylvania Station. Eventually, preservation came to provide security in the face of International Modernism by stopping the clock to freeze identifiable/uncluttered/singular/readable and safe moments in time. Uneasy with its modernity and fearful of the architectural anonymity of its times, America embraced the preservation movement for its provision of legacy—not unlike Mussolini’s cravings to substantiate his imperial claims. Propelled by this insecurity, presenting the historic landmark uncluttered by further additive readings became the preservationists’ and society’s unstated desire.

Codified by laws and guidelines, the preservation movement legislated architectural additions to the realm of banality when compared to a landmark’s original creative impetus. Essentially reduced to only two options, architects have either mimicked the existing, as in Kevin Roche’s seamless and slavish addition to New York’s Jewish Museum, or architects have disengaged from the objectified landmark as in the case of I. M. Pei’s self-absorbed addition to National Gallery. An utter inability to create a dialogue between past and present permeates both these strategies. History demands confrontation.

Jewish Museum, New York City

Jewish Museum, New York City

National Gallery, Washington D.C.

National Gallery, Washington D.C.

Throughout his writings, Aldo Rossi identified, termed and explored the polemic of urban artifacts. He clarified the difference in architecture between history and memory. For him, an urban artifact’s history, refers to the period when the architecture functions as designed. And memory, begins when the architecture ceases to function as originally programmed. Yet, is the issue of memory merely a recollection of preceding forms? What of the events and people that populated that site? For me, history refers not only to preceding architectural form, but to the collective memory of past events, occupants, contents, associations and aspirations.

Making evident such elusive memories establishes a dialogue between past and present, but are we capable of designing new structures that engage contextual memory? To do so, I believe requires the use of metaphors. The Latin root of the word metaphor, speaks of transference... can new architecture transfer history along with its myths, stories and lies?

While evoking a site’s past significance, architecture must also engage the present if we are to make that history pertinent. An architecture that evokes the past is irrelevant if it does not address current site conditions, meet new programmatic needs and satiate contemporary desires. These are the issues that have always motivated architecture. Though it's important to remember, that our architectural responses to such immediate needs will eventually cease to be relevant, as programs, aesthetics and emotions all change. Our architecture preserves the memories of time-specific agendas and will in due course become dateable archeological layers in themselves.

The mere preservation of a landmark, disengaged from contemporary agendas, is a vacuous goal. It is the layering of history, not the presentation of a cleansed idealized past, that awakens a site. To elucidate historical significance new constructions must engage inherent contextual memories, both in form and in program. Mine is a clear argument against the sterility of historic preservation. Though I illustrate my position through three proposals sited in Rome, this referential strategy is cross-cultural in nature and applicable to all sites of consequence. History, not historicism, should motivate our intentions, while never underestimating the power of wit.

3 propositions for the city of Rome:

Comments on the project: